As I mentioned in my last post, two years after my first visit, I would return one more time in 2002 to San Juan, Argentina and the Ischigualasto Provincial Park. Once again, I would volunteer for this fascinating fossil exploration led by Oscar Alcober and Ricardo Martinez. This post is about that second visit.

Introduction

Largely, the experience was very similar to the first, but with a few twists. One difference was that many students from the National University of San Juan joined us volunteers. Therefore, I got an opportunity to try to use some Spanish. I learned Spanish in high school but could never really converse with it. Many of the students only spoke Spanish so I couldn’t fall back on English all the time. It turned out to be quite painful; probably worse for them than for me. Additionally, because they were quite a bit younger than the typical volunteer, there was now some youthful energy to the event.

Once again, there were beautiful landscape scenes of the valley, including balanced rocks and the familiar younger Jurassic age red cliffs in the distance, along with a good sighting of a herd of Guanaco. Guanacos are basically like a desert version of Llamas. (See the last photo in the gallery below. Click any photo to see a larger version of the image.)

More Than Just Fossils

Unique to this visit, however, was that an Argentinian geology graduate student, Carina E Colombi, along with her thesis advisor from the University of Arizona, were working on something a little different alongside us. Rather than just researching the fossils themselves, their research involved understanding more about the climatic and geological conditions that predominated at the time the animals lived to get a sense of the environment these animals needed to adapt to.

I got to work with them for a portion of the time, which I found absolutely fascinating. They were looking for hardened nodules (I don’t recall exactly what they were made of) in the clay. The day I joined, there were four of us, Carina, her assistant, another younger university student, and myself.

I called the student my Spanish language tutor because she spoke no English, so I was forced to speak Spanish. It was painfully slow to communicate, however, because I had to use my Spanish/English dictionary to be able to understand or say anything. If only I could have stayed longer, I might have become more fluent.

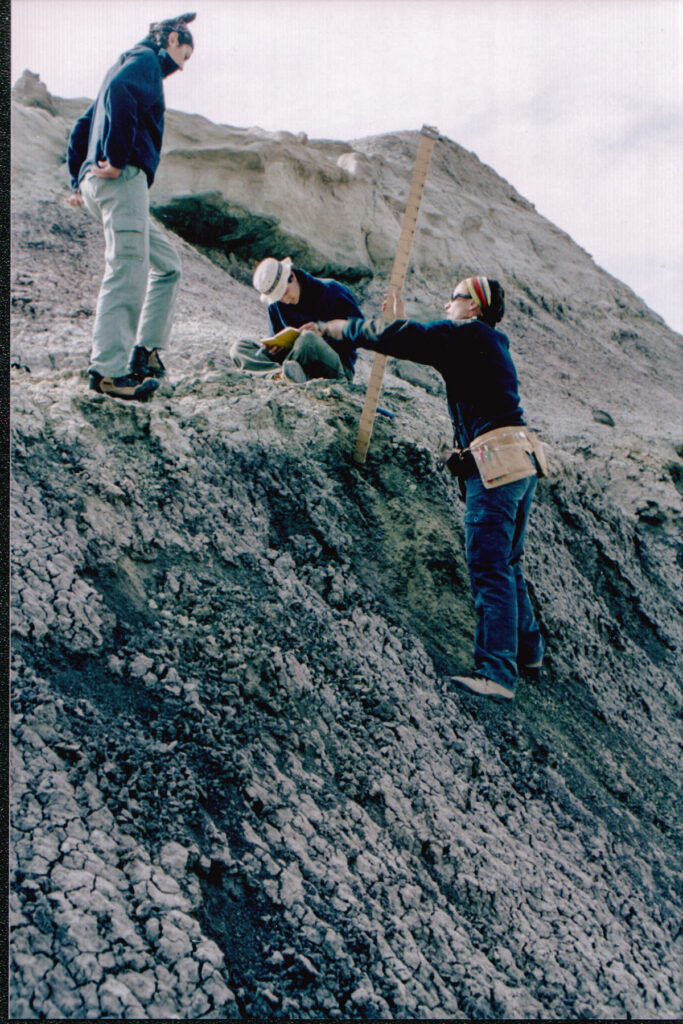

We initially drove out to the top of some tall bentonite hills. Then we would simply walk over the edge and step/slide down the hills on our feet. It was almost like skiing on dry dirt rather than snow. (Thankfully, it was dry, otherwise the dirt would become a thick clay that would stick to your boots, turning them into 10-pound weights.) We would stop, search for nodules, record information about them, and move on to another spot.

So, what were these nodules and what was their significance? The nodules were formed during rains way back in the Triassic and the size of the nodules indicated how heavy the rainfall was. The ones we were finding were roughly an inch in diameter. What they were finding from evidence around the world was that there were vast monsoons, 1000 times more powerful than the Indian monsoons of today, happening throughout the interior of the super-continent of Pangaea. Awesome!

Fossil Exploration

Of course, the main focus was to find fossils and the volunteers found a number of them. It is funny sometimes how memory works. I remember quite vividly what we found on my first visit. But looking at the photos of the fossils from my second visit, I am at a loss to remember what they were. Perhaps I was too busy thinking about nodules.

Fossil Extraction

But I do remember the preparation for extracting the fossils and that is where I could really get my hands dirty. What we had to do was define an area around a fossil and break up the rock around it using chisels and hammers. After a lot of back breaking work, we would create a moat around a central island where the fossil was.

Then it was time to plaster over the top of the island, by dipping burlap cloth into wet plaster and laying it flat and patting it down over the fossils. When the burlap and plaster would dry, it would hold the fossils in place to protect them.

Later, the large rock chunk with the fossil would be separated from the rock below and transported to the museum for the delicate work of removing the fossils from the rock. This lab work was not done by the volunteers because it required a lot of skill and a lot of time.

Volunteer Life

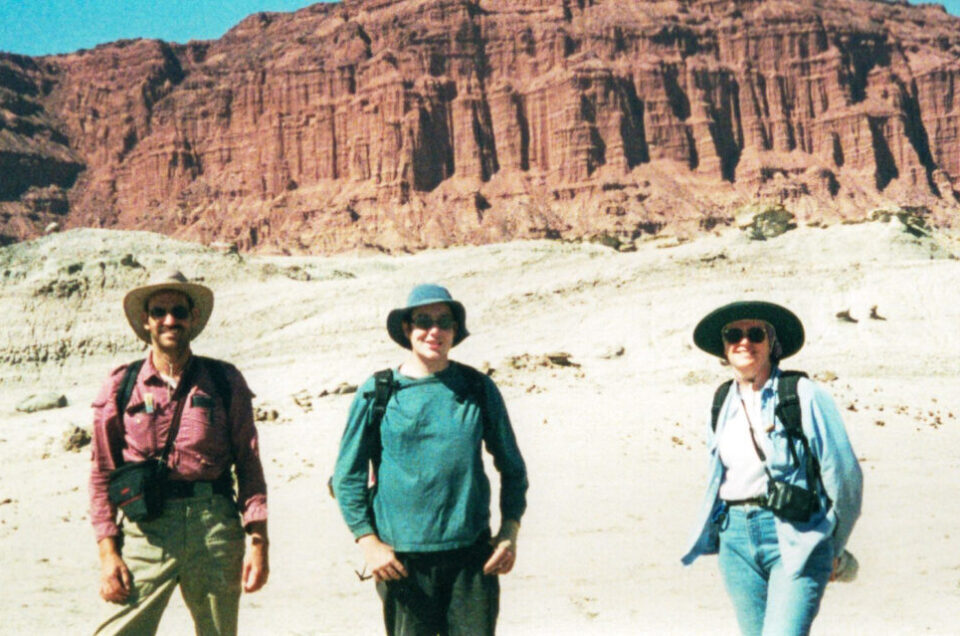

Below is a photo gallery of volunteer life during this visit, involving exploring or life at camp. Funny that somehow, I always end up in the picture with the young women students. I really don’t know how that happened.

But one cool fact is that the blue shirt you can see me wearing in the photos, I am still wearing today more than 22 years later. So, if you want a shirt that will last a lifetime, buy Columbia brand. (No, I will not receive any financial reimbursement for saying this.)

Conclusion

As it was two years earlier, this was quite the adventure. It was wonderful learning about the fossils, the methods, and the research. I wish I could have returned in future years. You will learn the reason I did not in my next blog post.

Lastly, though I continued to have an interest in paleontology, eventually I started to fall behind in keeping up with the latest developments. Recently, however, my wife has been writing blog posts about birds and during the process, learned some fascinating stuff about bird evolution. Her blog post is titled “The Feather“. I highly recommend reading it, so click the title to learn more.

Leave a reply